THE TATTOOED BODY

By putting colour into rather than on top of the skin, permanent markings can be created. Like body painting, this was probably also a chance discovery, the result of soot or clay getting into an open cut. Thorns or splinters of wood, bone, flint or shell could be used to puncture the skin to create deliberate permanent marks. More elaborately, a number of such sharp objects could be bound together and attached to a single wood or bone implement. Especially in the South Pacific, such clusters of sharp points were attached at a right angle to a stick, which could then be struck by another stick to drive the points into the skin. Distinctive tattooing technologies evolved among the Maori of New Zealand (their famous rrwko facial tattoos achieved by putting carbon pigment within scars chiselled into the flesh) and among Inuit populations where a needle and thread (smeared with soot) were drawn through the skin horizontal to the surface. As in Japan and many other cultures, tattooing in the West was traditionally done with straight needles of varying thickness and configuration, which were prodded under the skin. Except for an ever-expanding palette of colours, the only significant development in tattoo technology came in 1891 when Samuel O'Reilly patented the first electric tattooing machine in New York. (As the early 20th-century British tat-tooist George Burchett points out in his autobiography, there is an interesting irony in the fact that 'Tattooing, the most ancient of all beauty treatments, was the very first to make use of electricity.') But long before O'Reilly's 'tattaugraph', an extremely wide range of cultures throughout the world - from the Ukraine to Japan, Alaska to the South Pacific -had developed extraordinarily complex and graphically striking tattoo styles. The range, grace and complexity of so many of these styles obliges us to accord tattooing the status of one of humankind's most sophisticated artistic genres. Thatthis art form uses the living human body as its canvas underlines rather than detracts from its aesthetic accomplishments -for this is a genre that offers scant latitude for mistakes. How many of our great masterpieces of 'fine art' required the rethinking and adjustment that are unavailable to the tattoo artist?

As well as a formidable aesthetic achievement, the tattooed body demands respect as a system of communication. Arguably the most informative of all forms of body art, the symbolic functions of tattooing are particularly important in societies that lack written language - its images, pictographs, abstract design motifs, colours and positioning on the body (itself a primal symbol: the 'social body') providing a crucial databank of the knowledge, beliefs, values and history of so many traditional cultures. Additionally, the contrasting tattoo styles of particular individuals within a group often articulate and underline differences in role and status - immediately identifying the chief, those who have shown courage in battle or prowess in the hunt as well as who is (and who is not) a fully fledged adult member of the tribe.

Possessing written language does not. however, eradicate the significance of tattoo design as a valuable medium of expression. Many modern 'tribes' -Bikers, Skinheads, Punks, Mexican-American Chicanos and countless street gangs -have used tattoos both to mark the members of their group and also to articulate the world view of their subculture symbolically. However, in today's world, it is the language of personal, individual identity - rather than the language of social commitment and shared values - that the tattoo is most often called upon to express. Permanent andoften painful, the tattoo introduces amore radical approach to transforming appearance than those previously discussed. Western society went through along period of resistance to all such permanent decorations but in recent times this very quality, this challenge to transience, has contributed to the ever-growing appeal of both tattooing and body piercing. In much the same way, the pain and bloodletting inherent in the tattooing process - once seen as the crucial proof of its barbarism - has also recently become, for many, part of this adornment's appeal: an act that demands such a level of commitment and courage being seen as uniquely valuable in a world where valuehas arguably lost all meaning exceptthat of price.

When Captain James Cook 'discovered' Polynesia for the British in 1769, from a Western perspective he appeared to have discovered tattooing as well. Indeed, the English word for this technique of body decoration (and that of most European languages) derives from the Tahitian word tatu or tatau (to mark or strike the skin), which mimics the sound of one stick striking another to puncture the skin - the Tahitian technique of tattooing. Ironically, however, Europe has as much if not more historical claim to the invention of tattooing as does Polynesia. Perhaps people in the West in the 18th century had long forgotten the original meaning of previously used European terms for tattooing such as 'listing', 'rasing', 'packing', 'pinking' and 'pouncing'. Perhaps they had come to associate the older term 'stigma' (Latin, from Greek for 'marks on the skin', from stig-, the stem of stizein, 'to prick') only with the marks on Christ's hands andfeet (the plural, stigmata). Or perhaps, especially in the 18th-century Britain of Captain Cook, it was simply culturally convenient to forget such things. For once upon a time the shoe had been on the other foot: when the Romans 'discovered' Britain they called its inhabitants 'Picts' or 'painted people' because their bodies were covered in either body paint or, more likely, tattoos. At any rate, from the 18th century onwards, for Europeans tattooing became inexorably linked with the exotic - something that strange peoples in very distant lands didto their bodies. Westerners became fascinated by this remarkable phenomenon and paid to see exhibitions of imported tribal peoples and tattooed European men who claimed to have been kidnapped andforcibly decorated at the hands of barbarians. (A fascinating myth, but one that fails to understand that traditional peoples permit only those they honour to be tattooed.) Many who travelled to the Pacific - some explorers, and many sailors of all ranks - delighted in the tattoos that they acquired there. In later centuries, after Japan had been opened to the world in 1854 and the artistry of its tattoo masters celebrated abroad (while, ironically, outlawed at home for the Japanese themselves), many made the journey - most famously GeoTge V of Britain and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia - specifically to acquire such distinctive, exotic and beautiful decorations.

Another such Westerner was the aforementioned George Burchett, who applied the knowledge he acquired as a seaman in Asia to his work as a tattooist in London from 1900 to 1953. The American tattooist Gus Wagner was a seaman in the Pacific during the same period and when he set up his own tattoo parlour in Newark, Ohio, he brought knowledge (and even tools) he had acquired in Borneo and Java. Burchett, Wagner and many others brought a skill and imagination to their profession that produced many beautiful tattoos, but, in the main, tattooing as practised in Britain, Europe and America degenerated aesthetically to become hackneyed, two-dimensional, often crude and repetitive. Most customers were forced to choose from a standard set of near-identical 'flash' drawings found on the walls of studios from Hamburg to San Francisco, which were simply stencilled onto the skin with little or no sensitivity to placement on the body. Writing in 1953, in Pierced Hearts and True Love (one of the first general histories of tattooing), Hanns Ebensten describes such European and American tattoos as 'haphazard', 'hurriedly drawn and badly executed', 'spaced without thought or deliberation'andplaced'in an unpleasant relationship to each other'. Unfortunately, while there are some noteworthy exceptions, Ebensten was right about the standards of Western tattooing at that time. But while the general view is that blame for this aesthetic failure rests on artistically inept and money-hungry tattooists (of which, no doubt, there were many), it is more rewarding to consider how features of the Western world view made it next to impossible for even the most talented and dedicated European or American tattooist to equal or surpass the art of Japan or the technologically simpler societies of the Pacific. (Or that of the Scythians of the Ukraine some two thousand years ago: the body of a Scythian chief found preserved in permafrost possesses exquisite tattoos of real and imaginary animals positioned with breathtaking grace around his body.)

Unlike the Scythians, the Pacific Islanders, the Japanese and so many others, Westerners in their tattooing had not come to terms with the human body as a unique, three-dimensional object. Inevitably, this failure forces us to consider the West's problematic relationship with the human body itself. In the traditional Western view, the flesh is weak, it leads us astray, it debilitates and limits us and, most importantly, it is alien, extraneous, not us. (This peculiar attitude begins with Plato but was formalized by Descartes' famous dictum, which divides between physical and mental experience and equates being with the latter, ignoring the significance of the former.) Given such cultural baggage, is it any wonder that until recent times Western tattooists found it so difficult to approach the medium of the human body with the respect and delight that is so evident in other tattoo traditions?

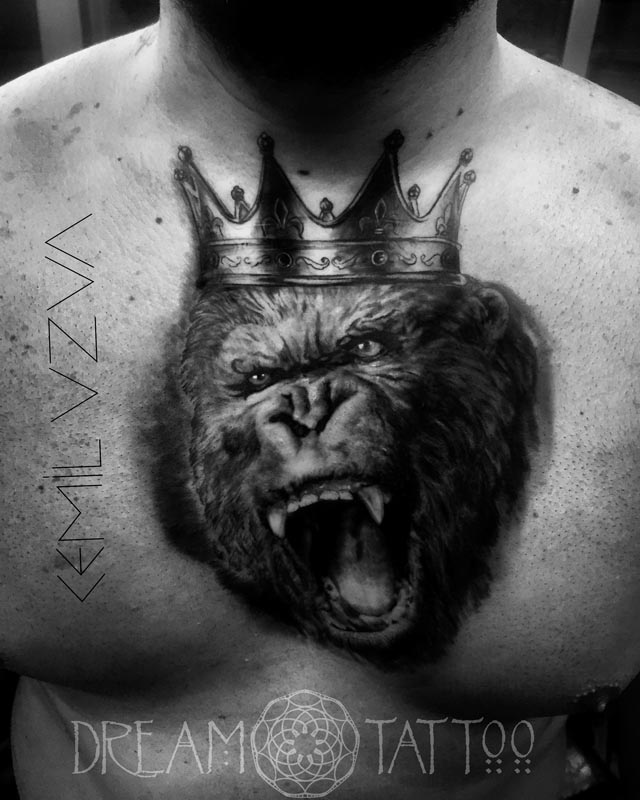

Whereas the Japanese or Tahitian tattooist had always worked with the body, the traditional Western tattooist seemed determined to cover it with art -in the process treating the three-dimensional body as if it were nothing but a two-dimensional blank sheet of paper. Andif it didn't occurtohim to use acon-sistent background to join together separate images into a visual whole (as the Japanese do), this is because, in the Western tattoo tradition, each image was executed as if on its own, separate, flat plane. (There is an interesting contrast here with Western cosmetic art, which, as discussed in the previous chapter of this book, almost always enhances, respects and celebrates the natural contours of the face. The key difference is gender. As Western men became increasingly estranged from their own bodies Western women were increasingly obliged to equate self with physicality. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that tattooing - a form of body decoration that existed in the West as an almost uniquely masculine adornment - should neglect the physical medium of the body in favour of the message inscribed on it, whereas cosmetics for women made and still make the medium of the face the message.) If the traditional Western tattooist was limited by his lack of respect for the human body, he also suffered from too much respect for the art world (which in the West, perhaps uniquely, had come to exclude body art from its domain). Striving to assert their own and their profession's artistic credentials, Western tattooists delighted in etching studies of'great' paintings onto their clients' backs and chests. And even when an image had no such fine art parentage, it was invariably drawn onto the skin in a painterly style. This persistence in trying to ape fine art inhibited Western tattooing from developing its own style - one more suited to its own tools and medium. It also kept tattoo art resolutely figurative: even when Western fine art discovered the possibilities of abstraction in the 1920s tattoos failed to follow suit. Until, that is, the 1960s - when a new generation of tattooists kick-started the 'tattoo renaissance'. As some of the fledging tattooists (for example, Cliff Raven and Ed Hardy) had been to art college in the 1950s and early 1960s, they brought with therrfa broader, 20th-century vision of what art could be - even embracing non-figurative styles such as abstraction. Alternatively, as in the case of the great pioneer of the tattoo renaissance 'Sailor Jerry' Collins, increased awareness of the aesthetic possibilities of tattoo art came from direct contact with tattooing in the Pacific. As discussed earlier, this was hardly the first time Western tattooists had directly experienced Eastern tattooing, but in the 1950s changing perceptions of both other cultures and the nature of art - together with a more positive view of the human body - meant that the likes of Collins and his followers could see the tattoo art of other peoples with fresh eyes. The tattoo renaissance may well have remained confined to the experiments of a handful of enthusiasts were it not for the youthquake and counterculture revolutions that shook the world in the second half of the 1960s. As well as a general questioning of mainstream cultural values and an accreditation of working/loweT-class styles, this systemic shift also, for many, recast the criminal outlaw as folk hero. All of these strands of rebellion pointed towards a more positive view of tattooing. If we were the people our parents warned us about then we really should get some tattoos. When the likes of Janis Joplin, Joan Baez and Peter Fonda got their 'tats' it finally opened the floodgates once and for all. As with the counterculture itself, a significant proportion of these new tattoo enthusiasts were middle-class and college or art-school educated.

This juxtaposition of a new type of tattooist and a new type of customer brought about a creative explosion that shattered the mould of traditional Western tattooing. Instead of making a quick (perhaps inebriated) choice of design from hackneyed, standardized flash drawings, the customer was now more likely to want unique, custom work -developed through a creative collaboration between client and tattooist.

Ancient styles from other, exotic tattoo traditions (Tribal, Japanese, Celtic) now joined with new approaches coming from Modern Art (a Kandinsky or Miro etched on human flesh), influences from streetstyle and pop culture to expand the tattoo lexicon dramatically. For the first time we see Western designs that are positioned to respect and complement the three-dimensional shape of the human body. True to the spirit of Postmodernism, eclectic stylistic elements from around the world and from different historical periods were merged on one body or even within one tattoo. The colour palette widened yet further and adventurous experiments in finding new tools and modifying old ones bore fruit. Hygiene standards were raised: needles and other equipment were scrupulously sterilized in autodaves.and leftover inks thrown away rather than shared between separate customers.

In another important demographic shift, female customers (and, increasingly, female professional tattooists) have become commonplace. While the West has long had tattooed women, they were previously seen as so freakish and unusual as to be exhibited in circus sideshows and the like.

Only a generation ago, tattooing (presumably because of the pain involved) constituted one, unique form of body adornment that didn't call into question a 'real' man's masculinity. But now, directly paralleling what has happened in clothing (it is difficult to find a woman today who doesn't wear jeans or trousers, but a man in a skirt or dress is still seen as atransvestite), the old masculine fortress of tattooing has been successfully stormed by the female sex. All these factors combined have made tattooing one of the most exciting and imaginative contemporary art forms. As can be seen at any of the growing number of tattoo conventions or on the pages of the many magazines and websites devoted to this body art, hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people are now actively engaged in stretching the aesthetic and stylistic possibilities of the tattoo.

- Mardin “Kızıltepe-Bozhöyük” Yöresinde Beden İşaretleri

- Tattoo tarihi (ingilizce)

- The Tattooed Body

- Pratical Advice on Getting A Tattoo

- Pain

- Aftercare

- Safety

- Reliability

- Cost

- A Final Word of Advice

- Pratical Advice on Getting A Piercing

- Preparing your body

- Your Piercing Appointment

- Immediately Before Piercing

- Aftercare

- Do use

- Avoid

- In case of Infection

- Healing Times

- Genitals

- Stretching

- A Final Word on Piercing